Emotional Regulation in the Workplace

A coworker said I look "content in my life and myself at work." I told her I think I accidentally look more "come at me, bro" most of the time. She laughed and said it's more like "Come at me, bro, and you can either meet my fist or get a hug. You decide; I don't care."

Honestly? That's probably the most accurate description of my emotional regulation strategy I've ever heard.

We all know that neurodivergent employees have higher burnout rates than neurotypical folks, and those statistics change depending on which flavor of brain spice you're working with. A Code First Girls study suggests that a whopping 90% of female neurodivergent employees are burning out in tech. Ninety percent.

The reasons are interconnected: sensory overload, social and communication challenges, lack of accommodations, stigma, and general misunderstanding. But today I want to focus on one that's particularly close to my heart and limbic system: emotional regulation challenges. Because here's the thing—emotional regulation isn't just about "maNaGIng yOUr FeEliNgs." It's about navigating a workplace designed by and for neurotypical brains while your brain processes everything, well… differently! It's performance art disguised as professionalism.

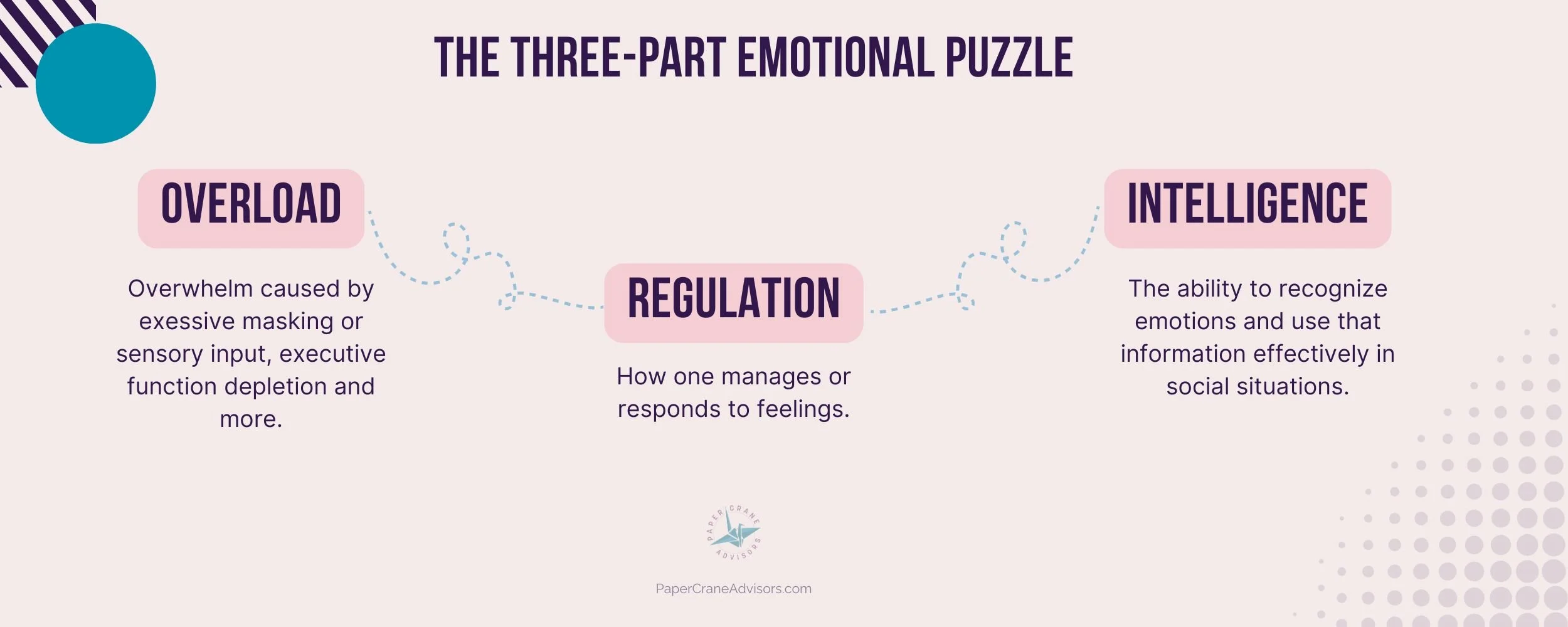

The Three-Part Emotional Puzzle

When we talk about emotions, there are really three interconnected pieces: Emotional Overload, Emotional Intelligence, and Emotional Regulation.

Emotional Overload

is when you get overwhelmed by feelings or emotions, usually caused by sensory overload (those fluorescent lights, the open office chatter, too many people in a meeting), executive function struggles that lead to anxiety (missing deadlines, unclear priorities), excessive masking, missing social cues, or just how your brain processes emotional stimuli in general.

Emotional Regulation

How you manage and respond to those feelings. We typically do this in two ways: reappraisal (reframing the emotional situation) and suppression (shoving it down deep and hoping it stays there).

According to research published in Clinical Psychology Science, neurotypical individuals tend to use reappraisal more effectively, while neurodivergent individuals often rely more heavily on suppression—which is cognitively exhausting and less effective long-term.

Emotional Intelligence (or EQ)

The ability to recognize emotions—both yours and others'—and use that information effectively in social situations. Employers love this "soft skill," which is ironic because for many neurodivergent folks, it's actually one of the hardest skills to master.

Here's the kicker: these three things don't operate independently. When you're emotionally overloaded, your ability to regulate suffers. When regulation fails, your emotional intelligence can go out the window.

It's like a Jenga tower made of feelings and workplace expectations >_<.

The Masking Marathon

The neurobiological differences that make emotional regulation challenging for neurodivergent individuals are well-documented. Research published in Nature Neuroscience shows that autistic individuals have different connectivity patterns in brain regions associated with emotional processing. And let's be real about what "professional emotional regulation" often means for neurodivergent folks: it's masking—performing neurotypical emotional responses while your actual brain is doing something completely different.

Research from University College London shows that masking is associated with increased anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation among autistic individuals. And for those with ADHD, that emotional masking contributes significantly to executive function depletion.

But emotional regulation challenges extend across the neurodivergent spectrum. Recent research in Frontiers in Psychology found that individuals with OCD, PTSD, anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorder "consistently face significant challenges in emotional regulation, recognition, and articulation." Otherstudies show that children with dyslexia are at elevated risk of internalizing mental health concerns and frequently experience anxiety as "the most frequent emotional symptom."

For individuals with PTSD, neuroimaging studies show alterations in the amygdala (fear processing), hippocampus (memory), and prefrontal cortex (executive control)—the exact brain networks responsible for emotional regulation and threat assessment. This isn't a deficit; it's a difference that requires different strategies.

A comprehensive study on workplace masking found that both autistic and non-autistic neurodivergent employees experience similar challenges, with participants frequently describing "symptoms of chronic stress, depression and anxiety" from masking their true selves at work.

I’ve spent years perfecting what I call the "Corporate Smile"—or as my best friends call it, "Pod Person Lex"—that slightly pleasant, engaged-but-not-too-eager expression that says "I am a reasonable human who will not cause problems in meetings." Meanwhile, my internal monologue was often some variation of "why are we having a meeting about planning a meeting?" or "if one more person uses 'synergy' unironically, I might actually scream; let’s just get this done!"

The exhaustion from constantly translating your authentic emotional responses into "workplace appropriate" ones is real and cumulative. And the worst part? Most workplaces mistake your masking for actual emotional regulation, so when the mask slips—because it always does eventually—everyone's surprised.

When Regulation Looks Like "Attitude"

What looks like poor emotional regulation to neurotypical managers might actually be a neurodivergent person's attempt at healthy boundary-setting or authentic communication.

Take my "come at me, bro" energy, for example. To some people, that might read as aggressive or unprofessional (especially as a woman). But what it actually is: me being direct about my capacity, clear about my boundaries, and honest about my emotional state without minimizing because I can't. At that point, I must be direct as that is the last of my emotional regulation in action.

Research published in the Academy of Management Journal found that when employees express authentic emotions like gratitude or sympathy while helping colleagues, they are perceived as having genuine motives, which enhances relationship quality and increases future cooperation. Yet neurodivergent individuals are often penalized for the same authenticity that would be valued in neurotypical employees.

Sometimes "good" emotional regulation for neurodivergent folks looks different from the neurotypical version:

Direct communication instead of emotional labor-heavy softening: "This deadline isn't realistic" rather than "I'm so sorry, but I'm wondering if there might be a way to perhaps adjust..."

Clear boundaries about capacity: "I can't take on additional projects this week" rather than "I'll figure out how to make it work somehow."

Authentic responses to unreasonable requests: "That doesn't make sense" rather than "Oh, interesting approach!”

The problem is that workplaces often interpret authenticity as "poor emotional intelligence" and boundary-setting as "difficult to work with" or "not a team player."

The Accommodation Conversation

You knew this was coming, right? Research by the Job Accommodation Network (JAN) shows that only 30% of employees with disabilities, including neurodiversity, feel their workplace is supportive enough to disclose their condition. Something you'll notice is that while many of these "accommodations" are for seemingly neurodivergent individuals, it benefits everyone in the workplace.

Asking for emotional regulation support feels vulnerable in ways that asking for a standing desk doesn't. It requires explaining that your brain works differently, that what looks like "attitude" or "sensitivity" is actually your brain wiring, and that you need different strategies to succeed—yet for some reason, it feels shameful and stigmatized.

But here's what effective emotional regulation support can look like:

Environmental accommodations: Noise-canceling headphones, flexible lighting, quiet spaces for decompression, minimizing sudden schedule changes. Sensory accommodations can reduce emotional dysregulation by up to 60%.

And here's a fun fact: research published in the Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health found that people in open offices had 62% more sick days than those in private offices. So perhaps this could be good for everyone...eh?

Communication adjustments: Written follow-ups to verbal instructions, clear agendas for meetings, advance notice of changes, direct feedback rather than hints. Multiple articles and research from places such as Harvard Business Review demonstrate that clear communication protocols benefit entire teams, not just neurodivergent employees.

Workload management: Realistic deadlines, clear prioritization, permission to focus on one task at a time, breaks between high-stimulation activities; structured work environments significantly improve performance.

Social navigation support: Clear expectations for meetings and social interactions, understanding that networking events might be draining, recognition that small talk is actual work for some brains.

Plot Twist: We're Often Really Good at This

Here's what many workplaces miss: neurodivergent employees often develop incredibly sophisticated emotional regulation strategies out of necessity. We become experts at reading rooms, managing our energy, and finding creative solutions to emotional challenges.

Autistic individuals often demonstrate superior analytical thinking and attention to detail precisely because of their different emotional processing patterns. ADHD individuals frequently excel at crisis management and creative problem-solving—skills that require sophisticated emotional regulation under pressure. People with OCD often develop exceptional quality control abilities and risk assessment skills—their heightened attention to potential problems can be invaluable in fields requiring precision and safety protocols. Research shows that individuals with OCD frequently demonstrate "exceptional attention to detail," "strong work ethic and dedication," and "advanced organizational skills" that make them highly effective in quality control, auditing, and analytical roles.

The issue isn't that we can't regulate emotions—it's that we're doing it constantly, at a level that would exhaust most neurotypical folks, while simultaneously trying to appear as if it's effortless.

Many of us develop what I call "emotional efficiency"—we cut through social niceties to get to the actual issue, we're direct about problems before they become crises, and we're often incredibly empathetic because we know what it feels like to be misunderstood.

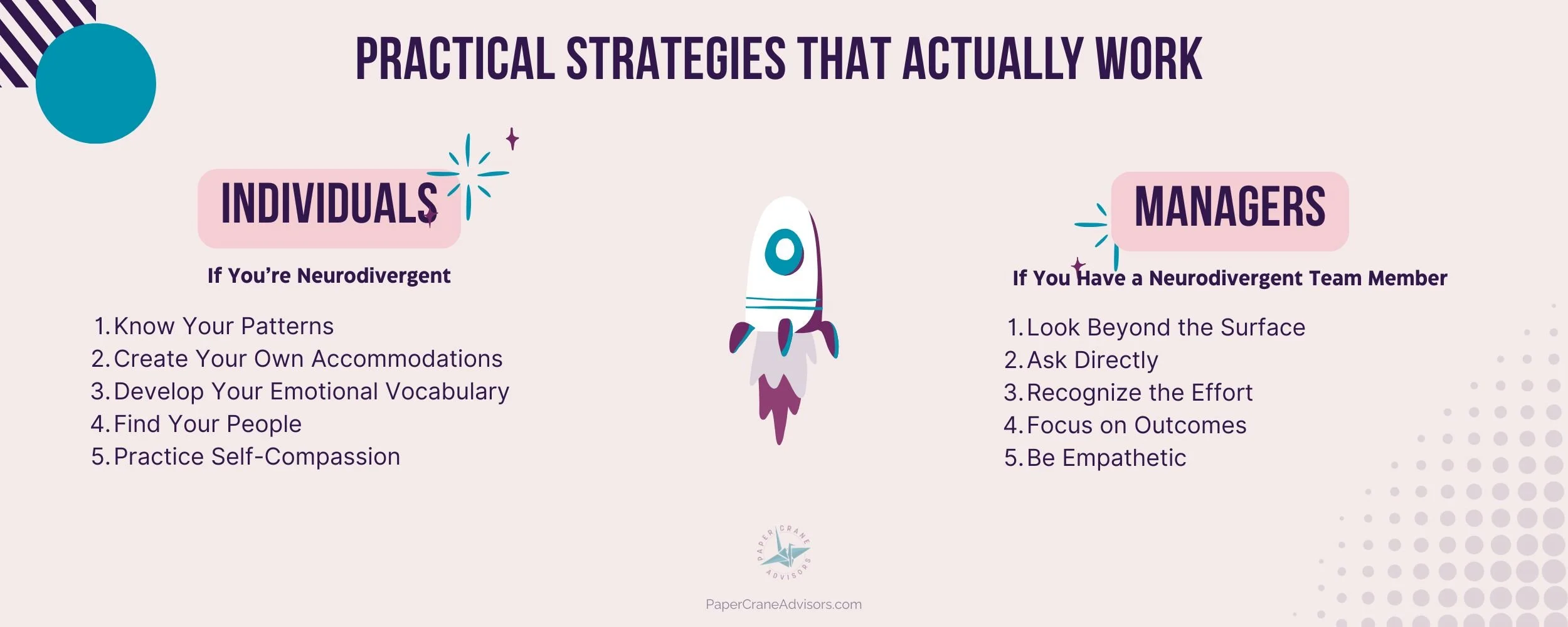

Practical Strategies That Actually Work For ICs and Managers

If you’re a neurodivergent human:

Know your patterns: Track when you feel emotionally overloaded. Is it after back-to-back meetings? During certain types of projects? When you're hungry or tired? Research shows that self-awareness is the strongest predictor of successful emotional regulation strategies.

Create your own accommodations: Even if you can't formally request them, find ways to support yourself. Take bathroom breaks for sensory breaks. Use noise-canceling headphones. Keep snacks at your desk. Self-initiated accommodations are often as effective as formal ones!

Develop your emotional vocabulary: The more specific you can be about what you're feeling and why, the easier it becomes to address it. "I'm overwhelmed" is less actionable than "I'm overstimulated by noise and need five minutes of quiet." Emotional granularity research demonstrates that specific emotional labeling improves regulation outcomes.

Find your people: Whether it's other neurodivergent colleagues, understanding managers, or online communities, having people who get it makes a huge difference. Social support research shows that understanding relationships significantly buffer workplace stress for neurodivergent individuals.

Practice self-compassion: Your emotional responses aren't wrong or broken—they're different. You're not failing at being professional; you're succeeding at being authentic in a system that wasn't designed for you.

If you're a manager or colleague of neurodivergent folks:

Look beyond the surface: That "attitude" might be burnout. That "sensitivity" might be sensory overload. That "rigidity" might be a coping strategy. .

Ask directly: "What kind of support would help you be most effective?" is often more useful than guessing.

Recognize the effort: Acknowledge that navigating neurotypical workplace norms is additional labor for neurodivergent employees. This recognition alone can significantly improve job satisfaction and retention.

Focus on outcomes: If someone's work is excellent and they are a professional human, does it matter that their emotional expression is different from what you expect?

The Bottom Line

Emotional regulation challenges aren't character flaws or professional deficits—they're neurological differences that require different strategies and support. And sometimes, what looks like "poor" emotional regulation is actually someone being refreshingly honest in a workplace full of emotional performance.

In a world full of toxic positivity and corporate emotional theater, maybe we need more people willing to say "This doesn't make sense" and "I need five minutes to process this" instead of plastering on that Corporate Smile and pretending everything is fine.

Your emotions aren't unprofessional. Your needs aren't unreasonable. And your different approach to emotional regulation might be exactly what your workplace needs, even if they don't realize it yet.

With 90% of neurodivergent women in tech burning out, we need to talk about emotional regulation—not as "managing your feelings," but as navigating workplaces designed for neurotypical brains while yours processes everything differently. What looks like "poor emotional regulation" to managers might actually be healthy boundary-setting or authentic communication. Your emotions aren't unprofessional, your needs aren't unreasonable, and your different approach might be exactly what your workplace needs.